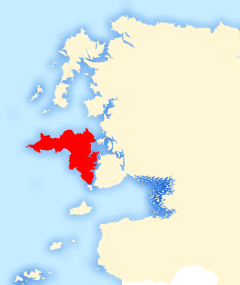

Achill Island

| Achill Irish: Acaill, Oileán Acla | |

Achill Head in the west of the island | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| Location: | 53°57’50"N, 10°0’11"W |

| Grid reference: | F686035 |

| Area: | 36,572 acres |

| Highest point: | Croaghaun, 2,257 feet |

| Data | |

| Population: | 2,569 (2011) |

Achill Island lies off the west coast of Ireland, in the wild Atlantic Ocean, and belongs to County Mayo. With an area of 57 square miles, it is the largest Island off the coast of Ireland. The island has a population of 2,700.

The island is 87% peat bog.

Achill is attached to the mainland by Michael Davitt Bridge, running between the villages of Achill Sound (Gob an Choire) and Polranny (Poll Raithní). A bridge was first completed here in 1887, replaced by another structure in 1949, and subsequently replaced with the current bridge which was completed in 2008.

Other centres of population include the villages of Keel, Dooagh, Dooega, Dooniver, The Valley and Dugort. The parish's main Gaelic football pitch and secondary school are on the mainland at Polranny.

Contents

History

It is believed that at the end of the Neolithic Period (around 4000 BC), Achill had a population of 500–1,000 people. The island would have been mostly forest until the Neolithic people began crop cultivation. The traces of settlements established on Achill have been dated to around 3000 BC: a paddle dating from this period was found at the crannóg near Dookinella.

Settlement increased during the Iron Age, and the dispersal of small promontory forts around the coast indicate the warlike nature of the times. Megalithic tombs and forts can be seen at Slievemore, along the Atlantic Drive and on neighbouring Achillbeg.

Achill Island lies in the Barony of Burrishoole, in the territory of ancient Umhall (Umhall Uactarach and Umhall Ioctarach), that originally encompassed an area extending from the County Galway/Mayo border to Achill Head. The hereditary chieftains of Umhall were the O'Malleys, recorded in the area in 814 AD when they successfully repelled an onslaught by the Vikings in Clew Bay. The Anglo-Norman invasion of Connaught in 1235 AD saw the territory of Umhall taken over by the Butlers and later by the de Burgos. The Butler Lordship of Burrishoole continued into the late 14th century when Thomas le Botiller was recorded as being in possession of Akkyll and Owyll.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, there was substantial migration to Achill from other parts of Ireland, particularly from Ulster, due to the political and religious turmoil of the time. For a while there were two different dialects of Irish being spoken on Achill, and this led to many townlands being recorded as having two names during the 1824 Ordnance Survey, and some maps today give different names for the same place. Achill Irish still has many traces of Ulster Irish.

In 2011, the population was 2,569. The island's population has declined from around 6,000 before the Great Famine.

Historical sites and events

Grace O'Malley's Castle

Carrickkildavnet Castle is a 15th-century tower house associated with the O'Malley Clan, who were once a ruling family of Achill. Grace O' Malley, or Granuaile, the famous Pirate Queen, was born on Clare Island around 1530.[1] Her father was the chieftain of the barony of Murrisk. The O'Malleys were a powerful seafaring family, who traded widely. Grace became a fearless leader and gained fame as a sea captain and pirate. She is reputed to have met with Queen Elizabeth I in 1593. She died around 1603 and is buried in the O'Malley family tomb on Clare Island.

Achill Mission

One of Achill's most famous historical sites is that of the Achill Mission or 'the Colony' at Dugort. In 1831 the Church of Ireland Reverend Edward Nangle founded a mission at Dugort, which included schools, cottages, an orphanage, an infirmary and a guesthouse. The Colony was very successful for a time, winning over many converts from the Roman religion, and regularly produced a newspaper called the Achill Herald and Western Witness. Nangle expanded his mission into Mweelin, where a school was built. The Achill Mission began to decline slowly after Nangle was moved from Achill and was finally closed in the 1880s. Nangle died in 1883.

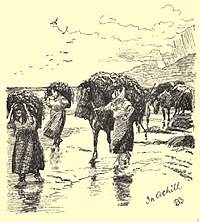

Railway

In 1894, the Westport - Newport railway line was extended to Achill Sound. The railway station is now a hostel. The train provided a great service to Achill, but it also is said to have fulfilled an ancient prophecy, albeit possibly one invented for the occasion; it was said that Brian Rua O' Cearbhain had prophesied that 'carts on iron wheels' would carry bodies into Achill on their first and last journey. In 1894, the first train on the Achill railway carried the bodies of victims of the Clew Bay Drowning. This tragedy occurred when a boat overturned in Clew Bay, drowning thirty-two young people. They had been going to meet the steamer which would take them to Scotland for potato picking.

The Kirkintilloch Fire in 1937 almost fulfilled the second part of the prophecy when the bodies of ten victims were carried by rail to Achill. While it was not literally the last train, the railway would close just two weeks later. These people had died in a fire in a bothy in Kirkintilloch. This term referred to the temporary accommodation provided for those who went to Scotland to pick potatoes, a migratory pattern that had been established in the early nineteenth century.

Kildamhnait

Kildamhnait on the south-east coast of Achill is named after St. Damhnait, or Dymphna, who founded a church there in the 16th century. There is also a holy well just outside the graveyard. The present church was built in the 1700s and the graveyard contains memorials to the victims of two of Achill's greatest tragedies, the Kirchintilloch Fire (1937) and the Clew Bay Drowning (1894).

The Monastery

In 1852, Dr. John McHale, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Tuam set aside land in Bunnacurry for the building of a monastery. A Franciscan Monastery was built which, for many years provided an education for local children. The ruins of this monastery are still to be seen in Bunnacurry today.

The Valley House

The historic Valley House is located in The Valley, near Dugort in the north-east of Achill Island. The present building sits on the site of a hunting lodge built by the Earl of Cavan in the 19th century. Its notoriety arises from an incident in 1894 in which the then owner, an English landlady named Agnes McDonnell, was savagely beaten and the house set alight, allegedly by a local man, James Lynchehaun. Lynchehaun had been employed by McDonnell as her land agent, but the two fell out and he was sacked and told to quit his accommodation on her estate. A lengthy legal battle ensued, with Lynchehaun refusing to leave.

At the time, in the 1890s, the issue of land ownership in Ireland was politically charged, and after the events at the Valley House in 1894 Lynchehaun was to claim that his actions were motivated by politics. He escaped custody and fled to the United States, where he successfully defeated legal attempts by the British authorities to have him extradited to face charges arising from the attack and the burning of the Valley House.

Agnes McDonnell suffered terrible injuries from the attack but survived and lived for another 23 years, dying in 1923. Lynchehaun is said to have returned to Achill on two occasions, once in disguise as an American tourist, and eventually died in Girvan, Ayrshire, in 1937. The Valley House is now a Hostel and Bar.

The Deserted Village

Close by Dugort, at the base of Slievemore mountain lies the Deserted Village. There are approximately 80 ruined houses in the village.

The houses were built of unmortared stone, which is to say that no cement or mortar was used to hold the stones together. Each house consisted of just one room and this room was used as a kitchen, living room, bedroom and even a stable.

If one looks at the fields around the Deserted Village and right up the mountain, one can see the tracks in the fields of 'lazy beds', which is the way crops like potatoes were grown. In Achill, as in many areas of Ireland, a system called 'Rundale' was used for farming. This meant that the land around a village was rented from a landlord. This land was then shared by all the villagers to graze their cattle and sheep. Each family would then have two or three small pieces of land scattered about the village, which they used to grow crops.

For many years people lived in the village and then in 1845 Famine struck in Achill as it did in the rest of Ireland. Most of the families moved to the nearby village of Dooagh, which is beside the sea, while some others emigrated. Living beside the sea meant that fish and shellfish could be used for food. The village was completely abandoned.

No one has lived in these houses since the time of the Famine, however, the families that moved to Dooagh and their descendants, continued to use the village as a 'booley village': the deserted houses would serve as shielings during the summer season, where the teenage boys and girls, would take the cattle to graze on the hillside as summer pasture. This custom continued until the 1940s. Boolying was also carried out in other areas of Achill, including Annagh on Croaghaun mountain and in Curraun.

At Ailt, Kildownet are the remains of a similar village, deserted in 1855 when the tenants were evicted by the local landlord so the land could be used for cattle grazing. The tenants were forced to rent holdings in Currane, Dooega and Slievemore. Others emigrated to America.

Archaeology

Achill Archaeological Field School is based at the Achill Archaeology Centre in Dooagh, which has served as a catalyst for a wide array of archaeological investigations on the island. It was founded in 1991 and is a training school for students of archaeology and anthropology. Since 1991, several thousand students from 21 countries have come to Achill to study and participate in ongoing excavations. The school is involved in a study of the prehistoric and historic landscape at Slievemore, incorporating a research excavation at a number of sites within the deserted village of Slievemore. Slievemore is rich in archaeological monuments that span a 5,000 year period from the Neolithic to the Post Mediæval. Recent archaeological research suggests the village was occupied year-round at least as early as the 19th century, though it is known to have served as a seasonally occupied booley village by the first half of the 20th century. A booley village (a number of which exist in a ruined state on the island) is a village occupied only during part of the year, such as a resort community, a lake community, or (as the case on Achill) a place to live while tending flocks or herds during winter or summer pasturing.[2] Specifically, some of the people of Dooagh and Pollagh would migrate in the summer to Slievemore and then go back to Dooagh in the autumn. The summer 2009 field school excavated Round House 2 on Slievemore Mountain under the direction of archaeologist Stuart Rathbone. Only the outside north wall, entrance way and inside of the Round House were completely excavated.[3]

From 2004 to 2006, the Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project directed by Chuck Meide was sponsored by the College of William and Mary, the Institute of Maritime History, the Achill Folklife Centre (now the Achill Archaeology Centre), and the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Programme. This project focused on the documentation of archaeological resources related to Achill's rich maritime heritage. Maritime archaeologists recorded 19th century fishing station, ice house, and boat house ruins, a number of anchors which had been salvaged from the sea, 19th century and more recent currach pens, a number of traditional vernacular watercraft including a possibly 100-year-old Achill yawl, and the remains of four historic shipwrecks.[4][5]

Other places of interest

The cliffs of Croaghaun on the western end of the island are the highest sea cliffs in the British Isles but are inaccessible by road. Near the westernmost point of Achill, Achill Head, is Keem Bay. Keel Beach is quite popular with tourists and some locals as a surfing location. South of Keem beach is Moytoge Head, which with its rounded appearance drops dramatically down to the ocean. An old observation post, built during First World War to watch for German ships, is still standing on Moytoge. During the Second World War this post was rebuilt by the Irish Defence Forces as a Look Out Post for the Coast Watching Service wing of the Defence Forces. It operated from 1939 to 1945.[6]

A mountain, Slievemore (2,205 feet), rises dramatically in the north of the island and the Atlantic Drive (along the south/west of the island) has some dramatic views. On the slopes of Slievemore is the Deserted Village.

Just west of the deserted village is an old Martello tower, built to warn of any possible French invasion during the Napoleonic Wars. The area also boasts an approximately 5000-year-old Neolithic tomb.

The villages of Dooniver and Askill have picturesque scenery and the cycle route is popular with tourists.

Kildownet Castle, also known as Caisleán Ghráinne, is a small tower house built in the early 1400s.[7] It is located in Cloughmore, on the south of Achill Island. It is noted for its associations with Grace O'Malley, along with the larger Rockfleet Castle in Newport.

Achillbeg ('Little Achill') is a small island just off Achill's southern tip. Its inhabitants were resettled on Achill in the 1960s.[8]

Economy

A number of attempts at setting up small industrial units on the island have been made, but the economy of the island is largely dependent on tourism. Subventions from Achill people working abroad, in particular in the United Kingdom, the United States and Africa allowed many families to remain living in Achill throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

In the period of Ireland's "Celtic Tiger" economy, fewer Achill people were forced to look for work abroad.

Agriculture plays a small role and the fact that the island is mostly bog means that its potential for agriculture is limited largely to sheep farming. In the past, fishing was a significant activity but this aspect of the economy is small now. At one stage, the island was known for its shark fishing, basking shark in particular was fished for its valuable liver oil.

There was a big spurt of growth in tourism in the 1960s and 1970s before which life was tough and difficult on the island. Despite healthy visitor numbers each year, the common perception is that tourism in Achill has been slowly declining since its heyday. Currently, the largest employers on Achill are two hotels.[9] In late 2009 Ireland's only turbot farm opened in the Bunnacurry Business Park.

As a popular tourist destination, Achill has many bars, cafés and restaurants which serve a full range of food. The island's Atlantic location ensures that seafood is a speciality on Achill with common foods including lobster, mussels, salmon, trout and winkles. With a large sheep population, Achill lamb is a very popular meal on the island too. Furthermore, Achill has a big population of cattle which produces excellent beef.

About the island

- The Great Western Greenway is a greenway rail trail that follows the line of the former Midland Great Western Railway branch line from Westport to Achill by way of Newport and Mulranny.[10] This has proved to be successful in attracting visitors to Achill and the surrounding areas.

Sport

- Gaelic athletics: Achill GAA, which has a Gaelic football club

- Football: Achill Rovers F.D.A.C.[11]

- Golf: There is a 9-hole links golf course on the island.>

Outdoor activities can be done through Achill Outdoor Education Centre.[12]

Achill Island's rugged landscape and the surrounding ocean offers multiple locations for outdoor adventure activities, like surfing, kite-surfing and sea kayaking. Fishing and watersports are also popular. Sailing regattas featuring a local vessel type, the Achill Yawl, have been popular since the 19th century, though most present-day yawls, unlike their traditional working boat ancestors, have been structurally modified to promote greater speed under sail. The island's waters and underwater sites are occasionally visited by scuba divers, though Achill's unpredictable weather generally has precluded a commercially successful recreational diving industry.

Literature

- Heinrich Böll: Irisches Tagebuch (Berlin 1957)

- Kingston, Bob: 'The Deserted Village at Slievemore' (1990)

- McDonald, Theresa: 'Achill: 5000 B.C. to 1900 A.D. Archaeology History Folklore' (I.A.S. Publications, 1992)

- Meehan, Rosa: 'The Story of Mayo' (2003)

- Carney, James: 'The Playboy & the Yellow Lady' (1986)

- Hamilton, Hugo: The Island of Talking': in the footsteps of Heinrich Böll, 50 years after (2007)

- Barry, Kevin: 'Beatlebone' (2015)

Outside links

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Achill Island) |

- Colaiste Pobail Acla students project on the Achill area

- Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project

- VisitAchill

References

- ↑ Lynch, Peter (2016-06-20). "The Pirate Queen of County Mayo". BBC. http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20160615-the-pirate-queen-of-county-mayo. Retrieved 2017-02-02.

- ↑ 'Deserted village, Slievemore, Achill Island' on achill247.com

- ↑ Amanda Burt, member of Achill Field School, Summer 2009.

- ↑ "Achill Island Maritime Archaeology Project | Institute of Maritime History". Maritimehistory.org. 20 February 2012. http://www.maritimehistory.org/content/achill-island-maritime-archaeology-project. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Meide Chuck (18 June 2014). "Meide, Chuck and Kathryn Sikes (2014) Manipulating the Maritime Cultural Landscape: Vernacular Boats and Economic Relations on Nineteenth-Century Achill Island, Ireland. Journal of Maritime History 9(1):115-141". Journal of Maritime Archaeology 9: 115–141. doi:10.1007/s11457-013-9123-3.

- ↑ See Michael Kennedy, 'Guarding Neutral Ireland' (Dublin, 2008), p. 50

- ↑ Irish Castles: Grace O'Malley on 'mythandlegends.net'

- ↑ Beaumont, Jonathan: 'Achillbeg: The Life of an Island' (2005) ISBN 0-85361-631-0

- ↑ "Achill Island (Co. Mayo)". Irelandbyways.com. http://www.irelandbyways.com/top-irish-peninsulas/the-west/the-western-isles/achill-island-co-mayo/. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ↑ Great Western Greenway

- ↑ FAI Club Portal for Achill Rovers

- ↑ Achill Outdoor