Oxford Castle

| Oxford Castle | |

|

Oxfordshire | |

|---|---|

St George's Tower, Oxford Castle | |

| Type: | Shell keep and bailey |

| Location | |

| Grid reference: | SP509063 |

| Location: | 51°45’6"N, 1°15’45"W |

| City: | Oxford |

| History | |

| Information | |

| Condition: | Ruined, elements used as a hotel |

| Owned by: | Oxfordshire County Council |

| Website: | oxfordcastle.com |

Oxford Castle is a large, partly ruined Norman castle in Oxfordshire on the western side of central Oxford. Most of the original moated wooden motte-and-bailey castle was replaced in stone in the 11th century and played an important role in the conflict of the Anarchy. In the 14th century the military value of the castle diminished and the site became used primarily for county administration and as a prison.

Most of the castle was destroyed in the Civil War and by the 18th century the remaining buildings had become Oxford's local prison. A new prison complex was built on the site from 1785 onwards and expanded in 1876; this became HM Prison Oxford.

The prison closed in 1996 and was redeveloped as a hotel. The mediæval remains of the castle, including the motte and St George's Tower and crypt, are Grade-I listed buildings and a Scheduled Monument.

Contents

History

Construction

According to the Abingdon Chronicle,[1] Oxford Castle was built by the Norman baron Robert D'Oyly the elder from 1071–73.[2] D'Oyly had arrived in England with William I at the Norman Conquest in 1066 and William the Conqueror granted him extensive lands in Oxfordshire.[2] Oxford had been stormed in the invasion with considerable damage, and William directed D'Oyly to build a castle to dominate the town.[3] In due course D'Oyly became the foremost landowner in Oxfordshire and was confirmed with a hereditary royal constableship for Oxford Castle.[4] Oxford Castle is not among the 48 recorded in the Domesday Book of 1086, but not every castle in existence at the time was recorded in the survey.[5]

D'Oyly positioned his castle to the west side of the town, using the natural protection of a stream of the River Thames on the far side of the castle, now called Castle Mill Stream, and diverting the stream to produce a moat.[6] There has been debate as to whether there was an earlier English fortification on the site, but whilst there is archaeological evidence of earlier Anglo-Saxon habitation there is no conclusive evidence of fortification.[6] Oxford Castle was clearly an "urban castle" but it remains uncertain whether local buildings had to be demolished to make room for it. The Domesday Book does not record any demolition, so the land may have already been empty due to the damage caused by the Norman seizure of the town.[7] Alternatively the castle may have been imposed over an existing street front which would have required the demolition of at least several houses.[8]

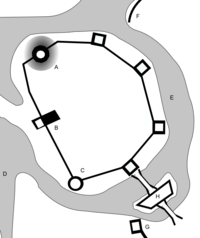

The initial castle was probably a large motte and bailey, copying the plan of the castle that D'Oyly had already built twelve miles away at Wallingford.[6] The motte was originally about sixty feet high and forty feet wide, constructed like the bailey from layers of gravel and strengthened with clay facing.[9] There has been debate over the sequencing of the motte and the bailey: it has been suggested that the bailey may have built first, which would make the initial castle design a ringwork rather than a motte and bailey.[10]

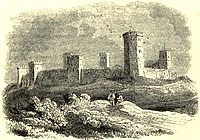

By the mid-12th century Oxford Castle had been significantly extended in stone. The first such work was St George's Tower, built of coral rag stone in 1074, thirty feet by thirty feet at the base and tapering significantly toward the top for stability.[11] This was the tallest of the castle's towers, possibly because it covered the approach to the old west gate of the city.[12]

Inside the walls the tower included a crypt chapel,[12] which may be the site of a previous church.[10] The crypt chapel originally had a nave, chancel and an apsidal sanctuary. It is a typical early Norman design with solid pillars and arches.[13] In 1074 D'Oyly and his close friend, Roger d'Ivry endowed a chapel with a college of priests. At an early stage it acquired a dedication to Saint George.

Early in the 13th century the wooden keep on top of the motte was replaced with a ten-sided stone shell keep of 58 feet, closely resembling those of Tonbridge and Arundel Castles.[14] The keep enclosed a number of buildings, leaving an inner courtyard only 22 feet across.[15] Within the keep, stairs led 20 feet down to an underground stone chamber twelve feet wide, with an Early English hexagonal vault and a well 54 feet deep providing water in the event of siege.[16]

Role in the Anarchy and Barons War

Robert D'Oyly the younger, Robert D'Oyly the elder's nephew, had inherited the castle by the time of the civil war of the Anarchy in the 1140s.[2] After initially supporting King Stephen, Robert declared his support for Empress Matilda, Stephen's cousin and rival for the throne, and in 1141 the Empress marched to Oxford to base her campaign at the castle.[17] Stephen responded by marching unexpectedly from Bristol in December, attacking and seizing the town of Oxford and besieging Matilda in the castle.[15] Stephen set up two siege mounds beside the castle, called Jew's Mount and Mount Pelham, on which he placed siege engines, largely for show, and proceeded to wait for Matilda's supplies to run low over the next three months.[14] Stephen would have had difficulty in supplying his men through the winter period, and this decision shows the apparent strength of Oxford Castle at the time.[18]

Matilda responded by escaping from the castle; the popular version of this has the Empress waiting until the Castle Mill Stream was frozen over and then dressed in white as camouflage in the snow, being lowered down the walls with three or four knights, before escaping through Stephen's lines in the night as the king's sentries tried to raise the alarm.[14] The chronicler William of Malmesbury, however, suggests Matilda did not descend the walls, but instead escaped from one of the gates.[18] Matilda safely reached Abingdon in Berkshire and Oxford Castle surrendered to Stephen the next day.[14] Robert had died in the final weeks of the siege and the castle was granted to William de Chesney for the remainder of the war.[19] At the end of the war the constableship of Oxford Castle was granted to Roger de Bussy before being reclaimed by Henry D'Oyly, Robert D'Oyly the younger's son, in 1154.[20]

In the Barons' War of 1215–17 the castle was attacked again, prompting further improvements in its defences.[21] In 1220 Falkes de Breauté, who controlled many royal castles in the middle of England, demolished the Church of St Budoc to the south-east of the castle and built a moated barbican to further defend the main gate.[22] The remaining wooden buildings were replaced in stone, including the new Round Tower which was built in 1235.[23] King Henry III turned part of the castle into a prison, specifically for holding troublesome University clerks, and also improved the castle chapel, replacing the older barred windows with stained glass in 1243 and 1246.[24] Due to the presence of Beaumont Palace to the north of Oxford, however, the castle never became a royal residence.[25]

14th–17th centuries

By 1327 the fortification, particularly the castle gates and the barbican, was in poor condition and £800 was estimated to be required for repairs.[26] From the 1350s onwards the castle had little military use and was increasingly allowed to fall into disrepair.[21] The castle became the centre for the administration of the county of Oxford, a jail, and a criminal court. Assizes were held there until 1577, when plague broke out in what became known as the "Black Assize": the Lord Lieutenant of Oxfordshire, two knights, eighty gentlemen and the entire grand jury for the session all died, including Sir Robert D'Oyley, a relative of the founder of the castle.[27] Thereafter assizes ceased to be held at the castle.[27]

By the 16th century the barbican had been demolished to make way for houses and the moat had begun to be occupied with housing. By 1600 the moat was almost entirely silted up and houses had been built all around the edge of the bailey wall.[28] In 1611 King James I sold Oxford Castle to Francis James and Robert Younglove, who in turn sold it to Christ Church College in 1613. The college then leased it to a number of local families over the coming years.[29] By this time Oxford Castle was in a weakened state, with a large crack running down the side of the keep.[30]

In 1642 the Civil War broke out and the Royalists made Oxford their capital. Parliamentary forces successfully besieged Oxford in 1646 and the city was occupied by Colonel Ingoldsby.[31] Ingoldsby improved the fortification of the castle rather than the surrounding town, and in 1649 demolished most of the mediæval stonework, replacing it with more modern earth bulwarks and reinforcing the keep with earth works to form a probable gun-platform.[32] In 1652, in the Third Civil War, the Parliamentary garrison responded to the proximity of Charles II's forces by pulling down these defences as well and retreating to New College instead, causing great damage to the college in the process.[31] In the event, Oxford saw no fresh fighting; early in the 18th century, however, the keep was demolished and the top of the motte landscaped to its current form.[30]

Role as prison

After the Civil War, Oxford Castle served primarily as the local prison.[33] As with other prisons at the time, the owners, in this case Christ Church College, leased the castle to wardens who would profit by charging prisoners for their board and lodging.[33] The prison also had a gallows to execute prisoners, such as Mary Blandy in 1752.[34] For most of the 18th century, the castle prison was run by the local Etty and Wisdom families and was in increasing disrepair.[35] In the 1770s the prison reformer John Howard visited the castle several times, and criticised its size and quality, including the extent to which vermin infested the prison.[36] Partly as a result of this criticism, it was decided by the County authorities to rebuild the Oxford Prison.[37]

In 1785 the castle was bought by the Oxford County Justices and rebuilding began under the London architect William Blackburn.[38] The wider castle site had already begun to change by the late 18th century, with New Road being built through the bailey and the last parts of the castle moat being filled in to allow the building of the new Oxford Canal terminus.[21] Building the new prison included demolishing the old college attached to St George's chapel and repositioning part of the crypt in 1794.[39] The work was completed under Daniel Harris in 1805.[40] Harris gained a reasonable salary as the new governor and used convict labour from the prison to conduct early archaeological excavations at the castle with the help of the antiquarian Edward King.[41]

In the 19th century the site continued to be developed, with various new buildings built including the new County Hall in 1840–41 and the Oxfordshire Militia Armoury in 1854. The prison itself was extended in 1876, growing to occupy most of the remaining space.[21] In 1888 national prison reforms led to the renaming of the county prison as HM Prison Oxford.

Today

Since 1954 the two oldest parts of the castle have been Grade-I listed buildings: the 11th-century motte with its 13th-century well-chamber,[42] and the 11th-century St George's tower with its crypt chapel and the 18th-century D-wing and Debtors' Tower.[39] The site is protected as a Scheduled Monument.

The prison was closed in 1996 and the site reverted to Oxfordshire County Council. The Oxford Prison buildings have since been redeveloped as a restaurant and heritage complex, with guided tours of the historic buildings and open courtyards for markets and theatrical performances. The complex includes a hotel in the Malmaison chain, Malmaison Oxford, occupying a large part of the former prison blocks, with cells converted as guest rooms. However, those parts of the prison associated with corporal or capital punishment have been converted to offices rather than being used for guests.[43] The mixed-use heritage project, officially opened on 5 May 2006, won the RICS Project of the Year Award 2007.

Outside links

| ("Wikimedia Commons" has material about Oxford Castle) |

- Oxford Castle

- Gatehouse Website record for Oxford Castle

- Oxford Castle Visitor Attraction

- Malmaison Oxford

References

- ↑ Referenced in Harfield, p.388.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Joy, p.28.

- ↑ MacKenzie, 147; Tyack, p.5.

- ↑ Amt, pp.47–8.

- ↑ Harfield, pp.384, 388–9.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 MacKenzie, p.147.

- ↑ Jope, p.79; Creighton, p.146.

- ↑ Tyack, p.5; Creighton, p.148.

- ↑ MacKenzie, p.148; Oxford Archaeology, accessed 12 September 2010.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Hassall 1976, p.233.

- ↑ Tyack, p.7; MacKenzie, p.148.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Tyack, p.6; Hassall 1976, p.233.

- ↑ Tyack, p.8.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 MacKenzie, p.149; Gravett and Hook, p.43.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 MacKenzie, p.149.

- ↑ Tyack, p.8; MacKenzie, p.149.

- ↑ MacKenzie, p.149; Amt, p.48.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Gravett and Hook, p.44.

- ↑ Amt, p.48.

- ↑ Amt, pp.56–7.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Hassall, p.235.

- ↑ Hassall 1971, p.9.

- ↑ Hassall 1976, p.235; Tyack, p.8.

- ↑ Davies, p.3; Marks, p.93.

- ↑ Munby, p.96.

- ↑ Crossley and Elrington, p.297.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Tyack, p.8; Hassall 1976, p.235; MacKenzie, p.149; Davies, pp.91–2.

- ↑ Hassall 1976, p.235, 254.

- ↑ Davies, p.3.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Oxford Archaeology, accessed 12 September 2010.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Joy, p.29.

- ↑ Joy, p.29; Oxford Archaeology, accessed 12 September 2010.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Davies, p.6.

- ↑ Davies, p.106.

- ↑ Davies, pp.9–10.

- ↑ Davies, p.14.

- ↑ Davies, p.15.

- ↑ Hassall 1976, p.235; Whiting, p.54.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 National Heritage List 1369490: St Georges Tower, St Georges Chapel Crypt and D Wing Including the Debtors Tower

- ↑ Hyack, p.7; Whiting, p.54.

- ↑ Munby, p.53; Davies, p.24.

- ↑ {National Heritage List 1369493: Well House Oxford Castle

- ↑ Smith, p.93.

Books

- Amt, Emilie. (1993) The Accession of Henry II in England: Royal Government Restored, 1149-1159. Woodbridge, Boydell Press]]. ISBN 978-0-85115-348-3.

- Creighton, O. H. (2002) Castles and Landscapes: Power, Community and Fortification in Mediæval England. London: Equinox. ISBN 978-1-904768-67-8.

- A History of the County of Oxford, Volume 4: The City of Oxford

- Davies, Mark. (2001) Stories of Oxford Castle: From Dungeon to Dunghill. Oxford: Oxford Towpath Press. ISBN 0-9535593-3-5.

- Gravett, Christopher and Adam Hook. (2003) Norman Stone Castles: The British Isles, 1066-1216. Botley, Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-602-7.

- Harfield, C. G. (1991). "A Hand-list of Castles Recorded in the Domesday Book". English Historical Review 106: 371–392. doi:10.1093/ehr/CVI.CCCCXIX.371.

- Harrison, Colin. (ed) (1998) John Malchair of Oxford: Artist and Musician. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum. ISBN 978-1-85444-112-6.

- Hassall, T. G. (1971) "Excavations at Oxford," in Oxoniensia, XXXVI (1971).

- Hassall, T. G. (1976) "Excavations at Oxford Castle: 1965-1973," in Oxoniensia, XLI (1976).

- Jope, E. M. "Late Saxon Pits Under Oxford Castle Mound: Excavations in 1952," in Oxoniensia, XVII-XVIII (1952–1953).

- Joy, T. (1831) Oxford Delineated: A sketch of the history and antiquities. Oxford: Whessell & Bartlett. OCLC 23436981.

- MacKenzie, James Dixon. (1896/2009) The Castles of England: Their Story and Structure. General Books. ISBN 978-1-150-51044-1.

- Marks, Richard. (1993) Stained glass in England during the Middle Ages. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-03345-9.

- Munby, Julian. (1998) "Malchair and the Oxford Topographical Tradition," in Harrison (ed) 1998.

- Smith, Philip. (2008) Punishment and Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-76610-2.

- Tyack, Geoffrey. (1998) Oxford: an Architectural Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-817423-3.

- Whiting, R. C. (1993) Oxford: Studies in the History of a University Town Since 1800. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-3057-4